1/34

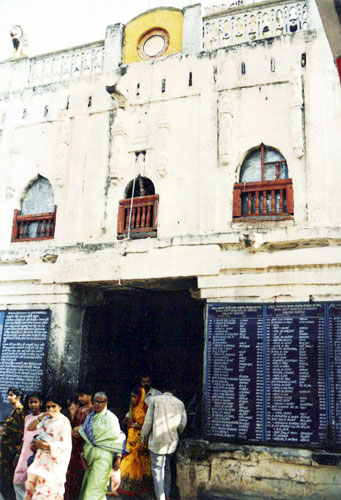

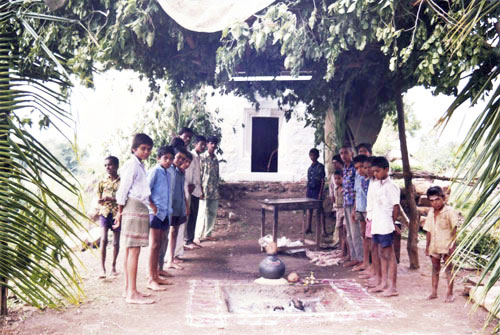

According to Abbé Dubois, who traveled widely in south India in the late Eighteeth Century, every temple of note had a band of eight or twelve devadasis in service. Royal or urban temples frequently had as many as four hundred. Beautiful and talented girls were transferred from small rural temples to royal temples along with elephants and horses.